Blood Test for Colon Cancer Screening

A new blood test is approved for colon cancer screening. What are its pros and cons, and how does it compare to the GRAIL Galleri test?

FDA recently approved a blood test for colon cancer screening. It is now an option in addition to colonoscopy or stool tests for colon cancer screening of those who are at least 45 years old. What are its pros and cons, and does it differ from the non-FDA-approved colon cancer aspect of multi-cancer detection blood tests such as the GRAIL Galleri test?

At 45 Years Old...

For the first colon cancer screening at age 45 for the average-risk patient, the most important thing is that it happens. As a primary care doctor, I saw the benefits a colonoscopy every 10 years had for detecting small polyps and resecting them to send to pathology. But many patients said, "No thanks!" Nor were they interested in doing a messy stool test collection. So this new blood test, while it has limitations, is wonderful to get more people routinely doing colon cancer screening.

Cancer Screening Recommendations

There are many dozens of types of cancers, but screening is only recommended for a handful of them. Cancer screening is only recommended if there is a demonstrated net benefit to doing the screening. A task force has been set up in the United States to scientifically review all the literature to make such recommendations. The summary below is oversimplified as each cancer recommendation may have subgroups where screening is or is not indicated or different grades of evidence for different subgroups.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force gives recommendations for cancer screening:

- Grade A

- high certainty that the net benefit is substantial.

- colorectal and cervical cancer screening.

- Grade B

- high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.

- cancer screening of breast, lung, and skin.

- Grade C

- recommends selectively offering or providing this service to individual patients based on professional judgment and patient preferences. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small.

- prostate cancer screening.

- Grade D

- recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits.

- pancreatic, ovarian, thyroid, and testicular cancer screening.

- Grade I

- current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined.

- bladder and oral cancer screening.

Shield

The major clinical trial that led to FDA approval was published in the NEJM. An FDA paper notes:

Shield is intended for colorectal cancer screening in individuals at average risk of the disease, age 45 years or older. Patients with an “Abnormal Signal Detected” may have colorectal cancer or advanced adenomas and should be referred for colonoscopy evaluation. Shield is not a replacement for diagnostic colonoscopy or for surveillance colonoscopy in high-risk individuals. The test is performed at Guardant Health, Inc.

The Guardant test demonstrated colorectal cancer (CRC) sensitivity of 83.1%, advanced adenoma (AA) sensitivity of 13.2%, and advanced neoplasia (AN) specificity of 89.6%.

The Guardant Provider Brochure states cell-free DNA is extracted from the blood plasma and prepared for genomic sequencing analysis. Guardant then explains: "The resulting cfDNA data are then analyzed using proprietary bioinformatics algorithms trained to detect the presence of colorectal cancer associated signals."

The Shield blood test has been well covered in the media, including the N.Y. Times. It noted a major limitation: "Unlike other screening tests for colon and rectal cancers, it has a poor record of finding precancerous growths. Removal of those growths can prevent cancer."

Shield vs. GRAIL Galleri

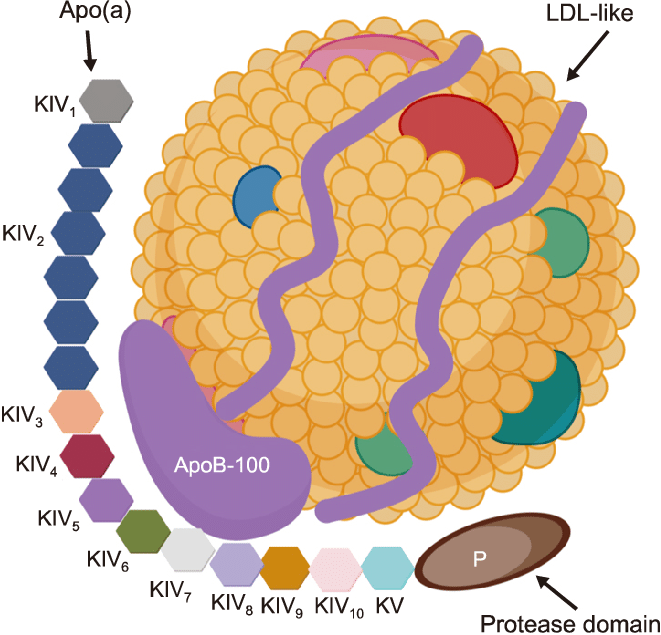

Both of these blood tests extract cell-free DNA from blood plasma and prepare the samples for genomic sequencing analysis.

Both cost in the $800-$1,000 range. However, given Shield's current FDA approval, health insurance will likely eventually cover it as a colon cancer screening option. This is generally not true for the GRAIL Galleri test. Out-of-pocket cost alone then virtually dictates the Shield test as the only way to go for most people. In addition, doctors want an FDA-approved test used, so for those patients declining a colonoscopy or a stool test, Shield is now the only way to go for colon cancer screening.

Each test will have its own proprietary bioinformatics algorithms to interpret the genomic sequencing analysis of the cell-free DNA extracted from the blood plasma. Since we do not have access to the algorithms, the only comparison we can make is via the reported sensitivity and specificity detection. Each company might continuously improve its algorithms as more data is collected. Now that Shield has FDA approval, they might need to get FDA sign-off on any changes they make to their analysis process.

GRAIL Galleri

This blood test looks at the blood plasma cell-free DNA to try to detect 50+ cancers, colon cancer being only one of them. As noted by the American Cancer Society: "This test is not FDA approved, but it is available under a CLIA waiver (because the testing itself is done in a central laboratory). This means doctors can order the test."

GRAIL recommends its Galleri test "for adults with an elevated risk for cancer, such as those aged 50 or older." The test can detect cancer signals of over 50 types of cancers, with varying sensitivities and specificities. For colon cancer, their reported sensitivity (proportion of true positives) was 82%. The Shield test's sensitivity was 83.1%, as noted in the above FDA paper and NEJM article.

Large clinical trials are underway to further evaluate the Galleri test, and it will likely eventually apply for FDA approval. If the trials show significant net benefits for detecting various cancers, the FDA may approve the test for that use. Such FDA approval, in turn, may lead to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force approving the test for cancer screening it already recommends and/or recommending new types of cancer screening that are not currently recommended.