DBP Too Low?

When the diastolic blood pressure goes below 70 and especially below 60, coronary artery perfusion can be compromised. This can result in worse cardiovascular outcomes.

When is blood pressure too low to be safe? Normal is under 120/80 to reduce your cardiovascular risk, and we all know high blood pressure is a major killer. But when checked at home or the gym, as I did recently, it was 84/54. I felt fine - not dizzy or lightheaded. Does this low diastolic blood pressure let me live longer, or is this bad? To answer this, we need to look at:

- Systolic blood pressure.

- Adequate non-cardiac organ perfusion is based on mean arterial pressure.

- Diastolic blood pressure.

- Adequate cardiac perfusion is based on diastolic blood pressure.

- Diastolic blood pressure J-Curve: What Is Optimal?

Systolic Blood Pressure

Systolic blood pressure is the higher number in a blood pressure reading. The goal is less than 120. Systolic blood pressure is when the heart pumps blood to the body's organs with the aortic valve open.

Adequate non-cardiac organ perfusion (e.g., kidneys) is based on mean arterial pressure (MAP). This is estimated by the formula:

MAP = DBP + (SBP - DBP)/3 (assumes normal heart rate)

Where DSP is the diastolic blood pressure, and SBP is the systolic blood pressure. Thus, when one has an ideal BP reading of 110/75, the MAP = 87. When at the upper limit of normal (119/79), the MAP = 92. My low reading (84/54) gives a MAP = 64.

Clinicians want to keep the mean arterial blood pressure above 60 to keep organs adequately perfused. A normal MAP is between 70-100. As UpToDate states: "While the optimal end-organ perfusion pressure is unclear, in general, we suggest maintaining the mean arterial pressure (MAP) between 65 and 70 mmHg..." (Evaluation of and initial approach to the adult patient with undifferentiated hypotension and shock, accessed 6/4/24)

So, from the viewpoint of mean arterial pressure being high enough to perfuse body organs outside the heart, even the BP reading of 84/54 is not bad. But there is more to the story in order for the heart to get enough blood.

Diastolic Blood Pressure

Diastolic blood pressure is the lower number in a blood pressure reading. The goal is less than 80. Diastolic blood pressure occurs when the heart is between contractions that pump blood to the body's organs and the aortic valve is closed. The heart relaxes and expands again, filling with venous blood to prepare for the next contraction that pumps blood through the aortic valve.

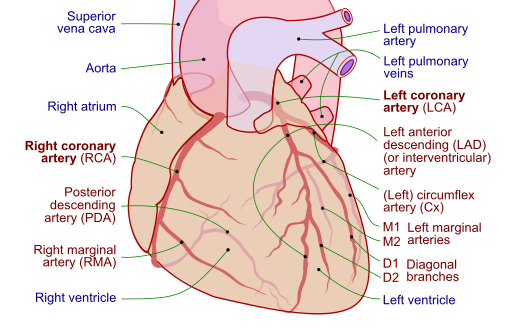

The heart itself gets most of its blood through the coronary arteries when the aortic valve is closed. Guyton & Hall (Textbook of Medical Physiology, 14th ed., pp. 262-3) note that the coronary artery blood flow is three times higher during diastole than systole. The reason, they explain, is the:

...strong compression of the intramuscular blood vessels by the left ventricular muscle during systolic contraction. During diastole, the cardiac muscle relaxes and no longer obstructs blood flow through the left ventricular muscle capillaries, so blood flows rapidly during all of diastole.

Therefore, the effective mean arterial pressure in the coronary arteries of the left ventricle for adequate perfusion is approximately the diastolic pressure. If the diastolic blood pressure drops below 60, cardiac ischemia of the left ventricle may occur.

As Messerli & Panjrath wrote in 2009:

The topic of the J-curve relationship between blood pressure and coronary artery disease (CAD) has been the subject of much controversy for the past decades. An inverse relationship between diastolic pressure and adverse cardiac ischemic events (i.e., the lower the diastolic pressure the greater the risk of coronary heart disease and adverse outcomes) has been observed in numerous studies. This effect is even more pronounced in patients with underlying CAD. Indeed, a J-shaped relationship between diastolic pressure and coronary events was documented in treated patients with CAD in most large trials that scrutinized this relationship. In contrast to any other vascular bed, the coronary circulation receives its perfusion mostly during diastole; hence, an excessive decrease in diastolic pressure can significantly hamper perfusion.

They go on to note:

The 22,576-patient INVEST study was an ideal model to analyze the significance of the J-curve, because all patients had CAD and hypertension. Indeed, the primary outcome in the INVEST study doubled when DBP was below 70 mm Hg and quadrupled when it was below 60 mm Hg. The nadir for DBP was 84 mm Hg. In contrast, the nadir for SBP was 119 mm Hg, and the curve between SBP and outcome was much shallower than with DBP.

So, the best outcome in this very large study group was when the blood pressure was 119/84. Bad outcomes (heart attacks) doubled when the diastolic was below 70 mmHg and quadrupled when below 60 mmHg. Of course, bad outcomes skyrocketed when blood pressures went too high also.

... found that an achieved DBP value of less than 60 mm Hg was associated with significantly increased risk of the primary outcome, the composite cardiovascular outcome, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke in a population with a guideline-recommended SBP target of less than 130 mm Hg. The nominally lowest risk was observed at an achieved DBP value of between 70 and 80 mm Hg for the primary outcome, the composite cardiovascular outcome (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction and nonfatal stroke), nonfatal myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular death in this population.

So, in this study, when the systolic blood pressure was less than 130, the best outcome on the J-curve (fewest strokes, heart attacks, and cardiovascular death) was when the diastolic blood pressure was 70-80 mm Hg.

A 2011 study (Guichard, et al.) looked at isolated diastolic hypotension (DBP<60) and incident heart failure in older adults. They found:

During >12 years of median follow-up, centrally adjudicated incident heart failure developed in 25% and 20% of matched participants with and without isolated diastolic hypotension, respectively (hazard ratio associated with isolated diastolic hypotension: 1.33 [95% CI: 1.10-1.61]; P=0.004). Among the 5376 prematch individuals, multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio for incident heart failure associated with isolated diastolic hypotension was 1.29 (95% CI: 1.09-1.53; P=0.003). As in isolated systolic hypertension, among community-dwelling older adults without prevalent heart failure, isolated diastolic hypotension is also a significant independent risk factor for incident heart failure.

So, in this study group of those 65 years of age or older, it was bad to keep diastolic blood pressure under 60 mmHg because it significantly increased your risk of getting heart failure.

A 2016 paper (McEnvoy et al.) "studied 11,565 adults from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study" and concluded:

Particularly among adults with SBP ≥120mmHg, and thus elevated pulse pressure, low DBP was associated with subclinical myocardial damage and CHD events. When titrating treatment to SBP <140mmHg, it may be prudent to ensure DBP levels do not fall below 70mmHg, and particularly below 60mmHg.

Because of the diastolic J-curve, my BP of 84/54 is too low. It is not making me live longer; it is putting me at risk for cardiovascular events. The diastolic of 54 is compromising coronary artery circulation, and adjustments should be made to increase it (hydration, replace electrolytes, adjust BP meds, etc.).

Diastolic Blood Pressure J-Curve: What Is Optimal?

Because of the J-curve, where heart attacks and other cardiovascular problems (strokes, heart failure, cardiovascular death) increase when the diastolic blood pressure is too high or too low, we want to keep the diastolic blood pressure in the optimal range for the lowest risk.

The current American guidelines (Whelton et al., 2017) set the blood pressure definitions in adults as:

- <120/80 is normal.

- <130/80 is elevated.

- <140/90 is hypertension stage 1.

- 140/90 or higher is hypertension stage 2.

If elevated, lifestyle changes are recommended to lower blood pressure (weight loss, less sodium, more potassium, DASH diet, exercise). If lifestyle changes are not enough, then the guidelines recommend medication for:

- Secondary prevention of recurrent CVD events in patients with clinical CVD and an average SBP of 130 mm Hg or higher or an average DBP of 80 mm Hg or higher. A BP target of less than 130/80 mm Hg is recommended.

- Primary prevention in adults with an estimated 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk of 10% or higher and an average SBP 130 mm Hg or higher or an average DBP 80 mm Hg or higher. A BP target of less than 130/80 mm Hg is recommended.

- Primary prevention of CVD in adults with no history of CVD and with an estimated 10-year ASCVD risk <10% and an SBP of 140 mm Hg or higher or a DBP of 90 mm Hg or higher. A BP target of less than 130/80 mm Hg may be reasonable.

- For older adults (≥65 years of age) with hypertension and a high burden of comorbidity and limited life expectancy, clinical judgment, patient preference, and a team-based approach to assess risk/benefit is reasonable for decisions regarding intensity of BP lowering...

However, the guidelines by Whelton et al. do not address how low is too low for diastolic blood pressure. From the above-cited studies, the optimal diastolic blood pressure associated with the lowest cardiovascular risk was:

- 84mm Hg (INVEST study), with 70-79 mm Hg being good (Messerli & Panjrath)

- 70-80 mm Hg has the lowest risk (Li et al.)

- Greater than 60 mm Hg (Guichard et al.)

- Greater than 60-70 mm Hg (McWnvoy et al.)

My conclusion is that if hypertension is not controlled by lifestyle changes and one needs to be on medication, then adjusting the medication dose to keep the diastolic in the 70s is best. I think most physicians would agree with this as long as the systolic was <130.

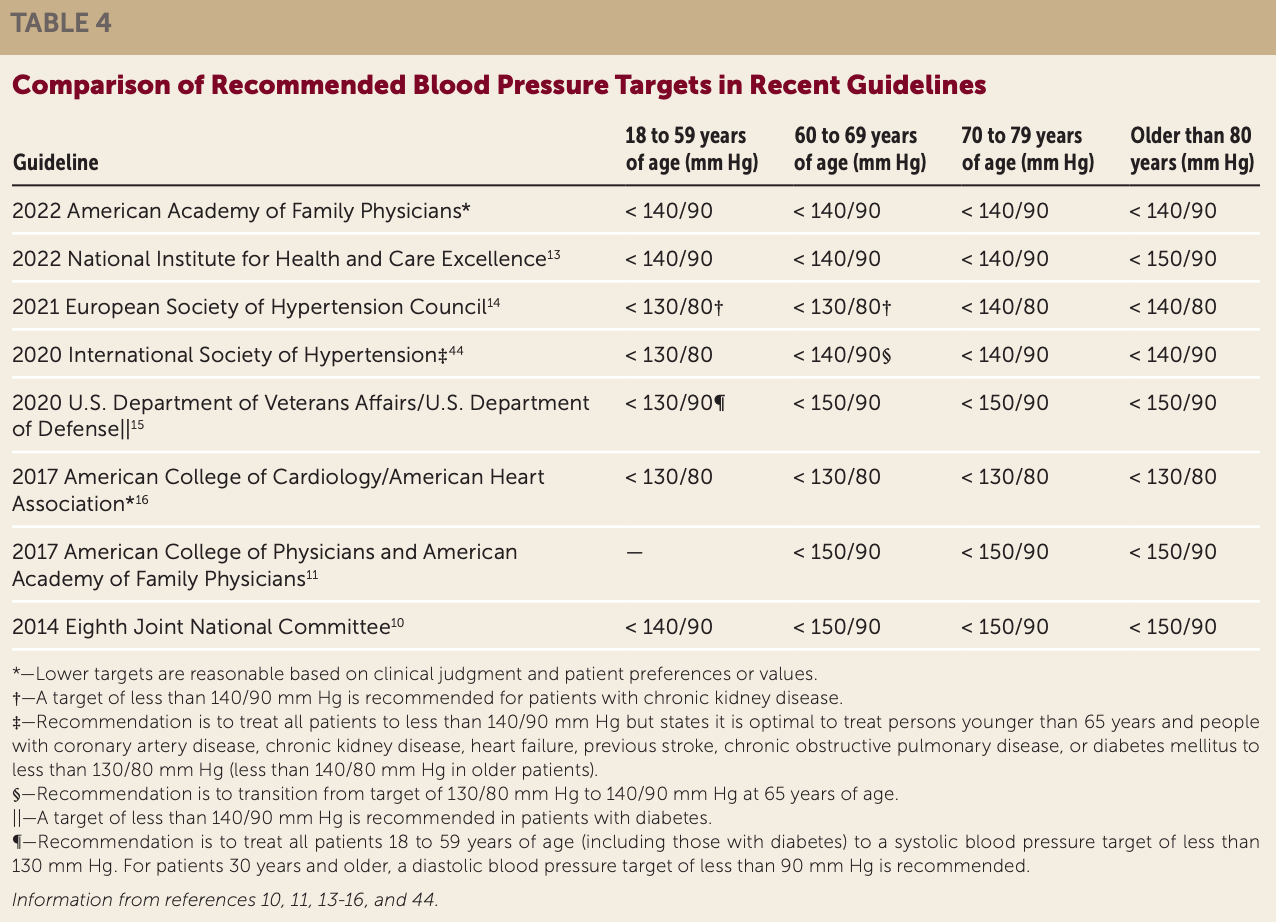

The more controversial issue is whether we should keep the diastolic at 70-79 if it means the systolic goes higher than 130. How high a systolic should we tolerate to prevent the diastolic from going too low? That is something to work out in dialogue with your physician, but it may be helpful to see other guidelines on how much control is recommended. Some of these are higher than the Whelton et al. guidelines either for everyone or those who are older.

Always talk to your doctor before making medication changes.

Audio podcast of this blog available on Spotify at https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/joe-breault-md-scd/episodes/Blood-Pressure-Too-Low-e2kjlla